If you want to be remembered properly, you would do well to write and publish your own story. If you are fortunate enough to have the editorship of a journal and enough influence over your association’s board, you can really secure your reputation for posterity. You can throw a festschrift, an event where scholars come together, your students and colleagues, and present papers honoring you and praising your contributions to knowledge and society. All the leading scholars have them. Typically they are organized by their graduate students, and some major press tends to publish the papers, gambling that a market exists for honoring you. But when you have juice and think enough of yourself, you can spend the Association’s resources on your greater glory. After all, ASALH could publish five rising scholars making new contributions to knowledge or honor yours at the same cost.

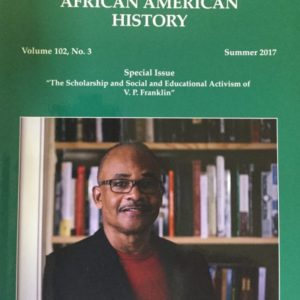

In this sense, V.P. Franklin has proven wise. Rather than leaving it to others, he took care of himself. We can assume that the Summer 2017 issue of the Journal of African American History, “The Scholarship and Social and Educational Activism of V. P. Franklin,” meets his approval. From his photograph on the cover, the contributors, to the ads running in the back, the special issue is the editor’s monument to himself. No other editor in ASALH’s illustrious history has had such recognition.

Indeed, Franklin has one-upped Carter G. Woodson in the house that he built. Our founder never had a special issue devoted to his work during his life or since. As he got older, he started to allow people to write about him, and when school children honored him with a book of short statements about his importance, it became one of his prize possessions. The teacher took the care of putting the handy-craft “book” in leather, and it served as his unpublished festschrift.

And it is in this light that we should understand V. P. Franklin’s role in ending the Woodson tradition of self-publishing. It was not about ASALH or Woodson, it was all about V. P. Franklin. Over the years he had had lots of difficulties in the production process of the journal, and among my jobs was smoothing things over with the company contracted to layout and copy edit the journal. Often unreasonable and intemperate, V. P. was always accommodated, but things became impossible, and the vendor wanted to quit. Not knowing a publisher from a printer, he also wanted new accommodations, and he went to university press behind my back as president and got bids. He did not know what was at stake. It was all about V. P. Franklin–his wants and needs. He gave no thought to what it meant to tradition. An advocate of black self-determination, he put his black self first.