In 2015, the University of Chicago Press, along with the University of California Press, pulled its journals out of JSTOR’s New Scholarship Program, and two years later, JSTOR, the most venerable of all the humanities and social sciences databases, has had to reshuffle its program for journals. By looking at the University of Chicago Press’s new model for hosting its own journals and JSTOR’s new offering to its publishers, we can learn much about the leading developments in hosting scholarship, new and old, where STEM is not concerned. What emerges from the darkness is the University of Chicago Press business model that makes it as interested in old scholarship as new. Put another way, it is playing the long game and it wants to take a chunk out of JSTOR’s main business–JSTOR Archive, which brings it most of its revenue. To succeed at this, it needs to sign up independent publishers and ask them to hand over control of their intellectual property, old and new.

The Dashed Hopes of Global Markets for American Humanities and Social Science Scholarship

Most academics, including those leading ASALH presently, seem to be oblivious to the reality that the market for humanities and social sciences journals is shrinking. When digital platforms like JSTOR, Metapress, and Project Muse appeared, it was hoped that global sales would make up for a declining domestic market. Recently, Oxford University Press, with its long-standing global footprint, has created digital platform for new scholarship, and major history journals such as the American Historical Review and the Journal of American History signed up. And over time, a number of university presses such as Duke and now Chicago and the University of California Press have entered the digital platform business. Chicago pretends it can increase your sales globally, but they do not have sales representatives abroad. Everyone else, including Chicago, has found out that there is not lots of money overseas. The humanities and social sciences are not hot overseas anymore than here. In fact, Japan, the most Western of the Asian nations, has announced it will shut down its state-run humanities and social science colleges entirely. That, of course, takes a lot of would-be libraries out of the market for American humanities and social science journals. Worse still, consortia are popping up in a number of countries, which is leading digital journal providers to sell their goods are dramatically reduced prices, and they are merely following the trend in the United States where consortia are popping along side athletic conferences. Then there are two other problems with increasing overseas sales. Some nations are not big on secondary and tertiary journals in any field, especially the humanities. They do not care to hear what every academic in America has to say, only the ones publishing in the leading journals. Why do they care to hear lesser known scholars in lesser known journals wax on pedantically. Finally, who cares about American humanities and social sciences all that much? Some folks are trying to spend their dollars on their own domestic and regional cultural and intellectual traditions. Why not let expand on their experiences using the same European theorists? Really, how much of this can anyone afford when STEM is taking over everyone’s journal budgets? With a declining domestic market and small foreign markets, the future of humanities and social sciences journals is bleak.

The Back Files Are Where the Humanities and Social Science Money Is

The academy’s appetite for old journals, called back files or archives, is greater than for new scholarship in the humanities and social sciences. Almost all libraries in America, ranging from universities to local libraries, buy the discounted back files. Indeed, librarians forced to cut a journal title from their collection console faculty by saying that we have the articles once they turn three years old, when they go into the archives (back files) of companies known as aggregators. If they are sophisticated, they tell them that most articles do not become important until they are available at a deep discount. The best known of the players in the journal archive business is by and far JSTOR; it is the gold standard among librarians. The other players are EbscoHost, Cengage, and ProQuest. We know most of the profitability of these archives by looking at JSTOR, which lives largely from their Archive even as they have recently branched out. By selling the back files of thousands of journals, they have made their parent company, Ithaka Harbors, a not-for-profit with $86,000,000 in annual revenue. Libraries do not pay back file providers much per title, but it is the volume of articles–millions of them–that brings in the lucrative contracts for JSTOR and others.

Back File Archives Are so Profitable Because They Cost So Little

With new journal subscribers dwindling, most publishers now regret signing contracts some twenty years ago that allowed the aggregators to scan and market their journals. No one had the money to scan the documents, especially if they had an eight or ninety years of journals. The money offered miniscule and the journals were still very profitable. The money for back files were seen as pure profit, money left on the table if one declined. And would you not want to be part of databases where the other journals would be? And what was the harm of this marginal technology? The articles would be made available on CD Roms, which would be used at a PC in a corner of the library. Print was still king. Oh, but then came the internet and the pdf, and electronic copies of a journal became a different thing. Today, no one would sign those contracts anew.

Article Archives Killing the Goose that Lays the Golden Eggs

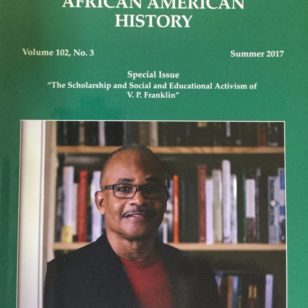

One can argue that in the humanities and social sciences the aggregators or archives are inadvertently killing the goose that laid the golden egg. If the libraries of the world can live with scholarly articles that are three years old or more in those fields, then how are the journals generating them supposed to survive? The aggregator money, which used to be 5 to 10% of the budget, is increasingly becoming 25% of the budget. I would not be surprised and I am praying that it does not become more than 50% of the budget for the Black History Bulletin and the Journal of African American History. I am sure that the University of Chicago Press and the University of California Press would not admit it, but they left JSTOR’s New Scholarship Program precisely because they were facing declining revenues. Given that they had dozens of titles, the declining revenue had to be addressed. JSTOR was charging them marketing fees, roughly 12% of sales, and that money was a waste. Yet by leaving JSTOR, they are cutting cost, not increasing revenue. Leaving JSTOR to reduce cost had to be coupled with a plan to make money.

Chicago and California Enter the Back Files Market

And low and behold, both Chicago and California now have a new product–back files for all their journals. Yes, they have entered the back file business. This strategy has two facets. First and foremost, by offering back files they can sell existing customers access to the whole run of the journals they publish for an additional subscription free, typically an additional thirty to forty percent. If a library does not want to pay for the large bundle of 2000 plus journals offered by JSTOR, they can buy the individual titles they truly need. And as important, the back files as a separate product solves an additional problem. When print was king, libraries would drop a title from their collection, it was gone forever. They would hardly ever renew a title once dropped because they would have to pay a premium to catch up the back issues. Sometimes the titles could not be replaced because they were out of print, and only over the years did companies come along to address that concern, but it would be costly. Now, however, with back files, this problem can be overcome easily digitally. But until recently this would be done via the subscribing to JSTOR’s Archive program. Chicago is probably hoping that with the back files program, they can be that solution and they can hope for better days in the academy and profit therefrom. Again, the long game.

Chicago Is Investing in New Journal Titles to Create Their Own Archive

As the very moment that humanities and social science titles are at the brink of insolvency even with JSTOR and Project Muse having been created to save them, the University of Chicago, wholly new to the digital platform world, is recruiting independent publishers like ASALH to join them. The lure is more, roughly $20,000 a year of black ink, for five years. Chicago has no way of increasing revenue in the shortrun, so this is a long-term investment. Chicago has been in the journal business for over a century. Perhaps they are betting that libraries will see better times. More likely, they are believing that by increasing the number of journals they publish will get hooked on the five-year contracts it will put them in a better market position–even if they lose money in the short run. After a decade of having their new stable of journals without new contribution to other companies’ archives, the value of those title will decrease for JSTOR and other aggregators but increase in value for Chicago’s new archive. So in a decade, their investment in new scholarship will pay off–it will be an investment that increases in value. And because they are requiring the back rights of their new customers, Chicago in a decade will have a way to make money even if new issues are not valuable in themselves. In this way, Chicago is trying to bite into the tens of millions that JSTOR makes on archives.

Chicago Is Asking for the Role of Publisher of Articles It Did Not Publish

To recover their initial investment, giving journals profits where they do not exist, the University of Chicago is asking for something JSTOR and other archives and aggregators do not ask–they are asking for the publisher’s position and a publisher’s pay–even for back files. Indeed, in exchange for five years of revenue guarantees that will certainly out pace the market, Chicago wants publishers rights to journals it had no role in publishing. It was 50% of the revenue of journals published a century ago–or last year. They are taking serious risk, so they hope for serious gain. They are arguing, in effect, your back files are worth pennies in existing archives but we will give your journal half of its take.

JSTOR throws a Monkey Wrench in Chicago’s Effort: Let Publishers Have More of Their Revenue from New and Old Scholarship

Having lost about a third of its journals with the pull out of Chicago and California, JSTOR has responded by ending their New Scholarship Program. In its place they are simply going to host new scholarship journals for scholarly societies without assuming a marketing role. They call it their Current Journals program. Rather than charging a 25% fee on revenue for all sales, JSTOR has implicitly acknowledged that it cannot replace domestic subscribers with global ones–no one can. Rather than continue to pretend that it can–as Chicago now pretending–it is acknowledging that the market for journals is at best flat and removing the premium being paid for marketing. In contrast to Chicago’s demand for a 50-50 split, JSTOR will charge a modest fee. For the price of an inexpensive website fee, and what amounts to inconsequential subscriber fee JSTOR’s Current Journal’s program is a no brainer for anyone who can see beyond what amounts to Chicago’s five-year signing bonus. In many cases, JSTOR’s fees structure will amount to savings greater than Chicago’s signing bonus. With JSTOR, you get virtually all of the gross revenues–between 92 and 95 percent. And you do not have to worry what happens after five years if Chicago’s program fails. Indeed, if subscribers for new scholarship continues to decline, there is no way for Chicago to pay the increasing amounts it implies you will make with them. Journals that were moved to Chicago will find their annual income drop as much as fifty percent in five years as the war on the humanities and social sciences continues.

Is Chicago Cynical?

Chicago is not coming clean with anyone with its business plan. Rather than stating that the past is more profitable than the present, it is indeed pretending that they are bullish on the future of new humanities and social science scholarship. In its marketing and its rhetoric, it is pretending they can double sales–which they have to do, or so it seems, to justify the bloated revenue promises. Even at ASALH those involved in weighing the Chicago Proposal cannot see how they are making money because the offer implies it will immediately double ASALH’s sales if they are going to break even. The members at the Annual Meeting were told that Chicago wants our Journal of African American History because it is a great journal and the University of Chicago is rich. How non-black firms are rationalizing this move is unknown, but Chicago is not irrational nor are they great philanthropists as any Southside boy knows. Chicago has an intention in making money and the tell lies in their insistence that they are treated like the publisher over all articles already published. That is the closest they come to being honest about how the past is at least as important as the future. They are pretending they were publishers of our journals all along and they are actually buying into that past with five years of bonus money. The moment of truth comes down the road.