It was a moment in ASALH history that I missed. It was the first Executive Council meeting of 2016, which took place in February. At issue was the future of publishing the Journal of African American History. I have heard several accounts of a presentation by an esteemed scholar, but since I was not there I don’t know anything for sure. I know there is a record–the minutes have been approved but not made available–and the presenter spoke, I’m told, from a prepared text. It was all very scholarly, strangely so for a board meeting. But lots of dust had been kicked up for the prior six weeks about taking the Journal of African American History to a white publishing establishment.

It was a moment in ASALH history that I missed. It was the first Executive Council meeting of 2016, which took place in February. At issue was the future of publishing the Journal of African American History. I have heard several accounts of a presentation by an esteemed scholar, but since I was not there I don’t know anything for sure. I know there is a record–the minutes have been approved but not made available–and the presenter spoke, I’m told, from a prepared text. It was all very scholarly, strangely so for a board meeting. But lots of dust had been kicked up for the prior six weeks about taking the Journal of African American History to a white publishing establishment.

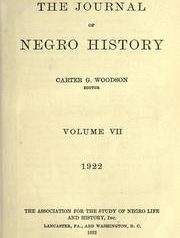

I am told that much was made about how ASALH had had publishers before. Part of the conversation centered around the role of a white firm out of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Could it be that someone mistook a printer for a publisher? I asked a number of people this but they kept saying publisher. But, really, the presenter had to been confusing printers and publishers. Or, I kept insisting to everyone asked, you have misunderstood what was being said.

I can see how one could confuse the printer for the publisher. It happens all the time. And it happened more back then because of laws governing the U.S. mail. It was long the case that printed materials being shipped had to register the point from which they were mailed, not just being published. Yet there, as always, on the title page, is the full name of the publisher and the place of publication. The publisher, of course, was the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, which had offices in Washington, DC. Now the folks with ink on their hands, whether they were white, black, or otherwise, were in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Nowhere on the title page is their name because they, after all, were not the publisher. The publisher’s name, dear scholars, holds that special place on the title page. We all know that.

Since I was not there and I am not privy to the facts of this matter, I am simply speculating that perhaps, just perhaps, someone confused the bossed for the boss, the functionary for the shot caller, the brawn for the brains, the printer for the publisher. As a black professor, I have been confused for a graduate student a few times myself. One day the record of this meeting will show whether folks got confused about the most fundamental tradition of ASALH. You see, if Woodson had had a white publisher, this journal of ours would not be the oldest journal published in the black world. The journal that we thought was published by us Negroes would have been published by the white man in the golden age of White Supremacy. Woodson’s reputation as an advocate of black self-determination would be ruined, too. History would show that he was just another front man, some puppet Negro whose strings were being pulled by his white overlords.

Clearly, this is just some misunderstanding between what was said and what was heard, or of what was said and what was meant, or of the practice of mistaking the part for the whole. To this very day, board members I talk to about this publishing issue are often confused on the matter, even as they continue to cast votes about it.