Nothing is worse in the non-profit world than having more money than ever before, except also believing your organization should have more status and prestige than it does. This combination led ASALH to what some of us know as the Que Street Debacle. A new headquarters building was bought and yet ASALH never moved into the building. How this million dollar mistake was made is a cautionary tale about the failure to perform due diligence and operate with transparency. It is a lesson that has been lost again by current members of the Executive Council.

After receiving a 1.5 million grant from the now defunct Wachovia Bank and selling the Woodson Home to the National Park Service, ASALH had a cash position of nearly $2.5 million, more than it had ever seen in its 90 year history. For nearly three years, ASALH had been a guest on Howard University’s campus and there were many who believed that ASALH now could afford a place of its own–having only sold its Fourteenth Street headquarters only a few years earlier to escape crushing debt. The national real estate boom was in full swing, and property seemed a sure thing.

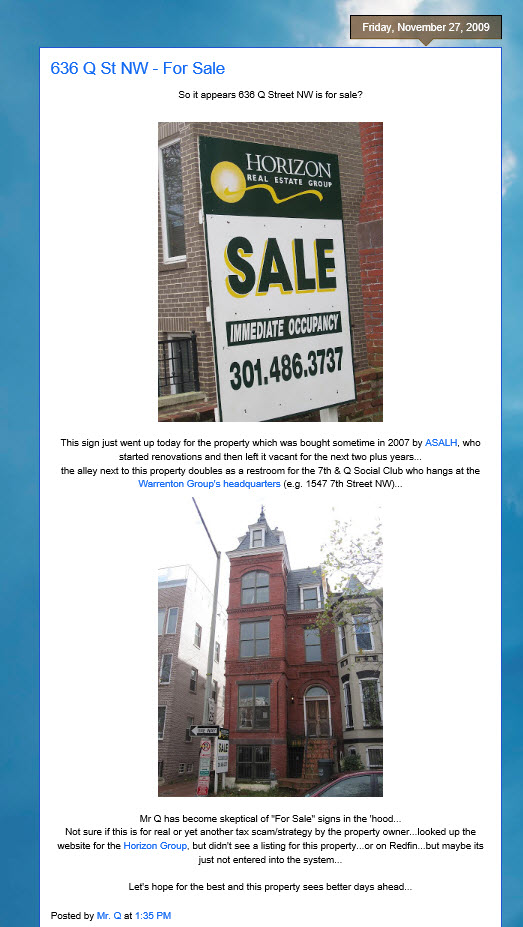

There were those who believed that ASALH should purchase a headquarters in Washington not far from Woodson’s home, and the property identified was 636 Q Street, NW. It was a residence, not a home, and it was said that the build out to make it functional as an office would be less than $150,000. The advocates of the position, led by a business person with vast experience in the hedge-fund industry, held that the building, once purchased, could qualify for a thirty-year municipal bond. Thus the fifteen-year loan that we would sign for would not matter so much as it would be temporary. Rather than take on a mortgage, or a mortgage alternative like a bridge loan, some of us believed that ASALH should relocate the headquarters to Maryland, where we could pay cash for a business condominium. The total cost, with build-out, would have been no more than $500,000 and ASALH would headquarters free and clear. Effectively we would have spent no more than we had made from the sale of Woodson’s home.

Before the Executive Council meeting, I argued the case for moving free and clear to Prince George’s County, and Rev. Richard T. Adams, whom I admire and consider my reverend, argued for staying in the city. Few would forget how he waxed on about how ASALH needed to be in the city, the nation’s capital, and not in the “cow pasture.” We all chucked at his humor, and most of the people on the board agreed with him. With the transaction in the hands of the hedge-fund manager and the incoming president of ASALH, no one else on the board, including me, felt compelled to examine the documents. In short order, we owned a building–the now notorious Q Street, and we would move in as soon as the modifications had been made.

ASALH never moved into Q Street. Although only authorized to make expenditures of approximately $150,000, the board member in charge of the project submitted bills for substantially more. Efforts were made to reign in the spending but the president’s efforts were rebuffed, and additional amendments to the contracts were signed. There was the unexpected new roof, termite abatement, facade shoring up, and numerous other challenges. Before all was done, the rehabilitation had run up to $500,000–and we still did not have a building that could pass inspection for occupancy. By this time the board member conceded that ASALH’s project would no qualify for a municipal bond–the size and the scale of the project, among other things, were inadequate for the minimum bond that the city would float. The hedge-fund guy who glibly talked about municipal bonds knew nothing about them! But that was not the bomb, nope. Brace yourselves, we had been lied to about the terms of the mortgage. It was not a fifteen year instrument. Nope, the mortgage was for five years–amortized over fifteen years–with a $600,000 balloon payment due January 1, 2012. Translated, the amount you would pay if you had a fifteen year mortgage but at the five year mark the rest of the money owed came due. Someone had signed a mortgage without appreciating or reporting the terms, believing, it seems, what we had all been told. The balloon had the ability to take the association under in three years. This is unfortunate for us. We know there were more affordable mortgages available. There are even mortgages to help new residents, allowing them to apply through their international credit reports, so they are able to settle in the states.

With great effort the project was brought to a halt. Leans were placed on the property by the building contractor and vendors involved, and bad feelings were everywhere because assurances had been given that we had the money to complete the project. Q Street became my mess to clean up. Everyone involved ran for the hills. Over the course of more than a year, I negotiated with the contractors and disabused them of the notion that would could honor our contractual agreements and survive as an organization. Eventually they let us out of the contracts, and Q Street became our unoccupied shell, would be headquarters. Under the presidency of Jim Stewart, we were able to sell the building at a great loss–having lost just under a million dollars on the project. Yet we were simply glad that we succeeded in selling before the balloon payment had taken us under.

So here we find ourselves once again business person, Gilbert Smith, lending his professional credential to persuade the board and the organization down a dubious path. While it is not his idea, he has lied about the Chicago Proposal. He and those involved have not done due diligence and vetted Chicago’s business plan, and no one has provided a cost benefit analysis. Worse still, the central documents have not been shared with board members and those who know most about the business affairs of the journal. Members are supposed to trust people who know nothing of publishing who have already been caught literally lying, representing revenue as profits. And to shut down opposition, they have resorted to efforts to stifle open debate and to overriden the constitution’s provision that allows the Business Session to make decisions that are binding on the board. The Que Street debacle may have cost a million dollars, but this debate over self-publishing has trampled over any notion of democracy and good governance.

(More on Q Street can be found in Duke’s Archives. Scholars interested in writing about Que Street may also contact me for my files. You can still find videos on the final renovation on YouTube. The new owners got a half-million dollars of free work from our debacle.)