At the 101st Annual ASALH Business Meeting, when she tried to justify signing a contract for the University of Chicago to publish the Journal of African American History, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham pointed to a 1920 effort by Woodson to get the integrated National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to purchase (not simply publish) the Journal. Providing no context, she believed his effort proved that Woodson was willing to work with whites–as if ASALH had not always worked with whites. The issue was self-publishing–being ultimately in control over the content, financing, and legal liability of the journal–not selling to or working with whites. As a historical matter, she begged the question: Why was Woodson trying to permanently let go of the Journal of Negro History? Indeed, at the time it was virtually ASALH’s first and only program, and it was the reason he founded the Association. What was going on in the Winter of 1920?

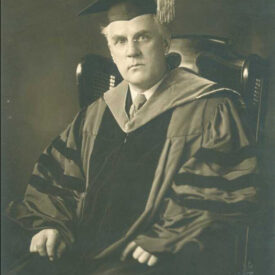

As it turns out, the first part of 1920 was a period of great personal and professional travail for the Founder. In summer of 1919, years after taking his doctorate at Harvard, Woodson finally was able to leave the District of Columbia Public Schools and become the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the Howard University. Yet it was a move that proved almost fatal to the Association and the Journal of Negro History. Within no time Woodson fell out with the white president of Howard, James Stanley Durkee, who was also in his first year as president of the university. Within the campus circle, their dispute over matters large and small were open discussions in print. He refused to monitor whether his faculty attended religious services as required; he opposed red-baiting, censorship of the library, and he sought to establish, without permission, an extension program for district teachers. By the end of his first semester, Woodson started looking for funding for the Journal, seeming to know he was unlikely to last more a single academic year at institution called the capstone of Negro education.

His disputes with President Durkee mattered greatly for the Association, especially the Journal, because Woodson had been its main source of funding. Over the previous five years, he had been putting $1,500 a year–$35,000 a year today with inflation–into the Journal. He had been paying for it with his job as a teacher and then a principal in the public schools. His move up in the world appeared to be his professional undoing. Soon, he recognized, he would need a source of revenue for his own survival and would not be able to care for the Journal that he breathed life into. Ironically, he had previously thought of Howard as a potential home for the journal, and six months after taking his post, the potential solution had become the problem.

The fact that Woodson needed to invest so much of his personal resources into the Journal is a sad testimonial about the state of the Association’s board. Clearly, the members were not doing as board members have always been expected to do–give money or get money–for the operations of the Association. The idea that Woodson could approach the NAACP on his own and attempt to sell the property of the Association speaks volumes. He could make such a presumptuous move because he was paying the freight that was the board’s obligation. Like many directors, he had bosses who could tell him what to do even if as they neglected their charge. Yet, the limits of their power ended with Woodson’s self-funding of what amounted to his Journal and his association. For certain, they could have stopped the sale of the Journal but they would not have been able to keep it alive unless they were willing to pay for an editor and pay for costs of the Journal. Had they been willing to do that the crisis would not have existed.

Trying to sell the journal was not his only out of character behavior. Though never the radical or black nationalist some scholars have thought him to be, Woodson was a progressive liberal, a member of the local branch of the NAACP, and an advocate of greater democracy. It was during this moment of desperation that Woodson found himself exposed by the Washington Bee for behaving radical and public and posing as a conservative to a powerful white Senator in hopes of raising funds for the Journal. In a public meeting in Washington, Woodson called the socialist A. Philip Randolph a prophet to great public applause.

For anyone who thinks of Woodson as a radical and a black nationalist, this letter is an eye opener. Here’s Woodson’s often repeated position that the Association should stay above politics and history should not be political is revealed to be signal to whites with money or access to it that his objectivity was the better alternative to the approach of “hot-headed radical” only seeking to make a name for themselves. Rather than seeking to empower black people through self-knowledge–that ethnic if not black nationalist approach to identify building–Woodson here suggested that the goal was to “interpret the Negro to the white man” to ease negative white attitudes towards black people. Here was the accommodationism of Booker T. Washington, not the militancy of Du Bois, Trotter, and now Randolph.

Woodson’s response to his Janus face being revealed by the Washington Bee is unknown, but his resort to playing to conservatives is a measure of the desperation he felt for the survival of the journal that he was soliciting funds from to keep the Journal and the Association alive. Within six months, the selling of the journal to the NAACP and the currying favor of powerful conservative whites came to an end. No sooner than he “resigned” from Howard, he was hired by John A. Davis, the president of West Virginia Institute for Colored Youth, both efforts stopped. A fellow member of the Washington, DC NAACP, Davis provided Woodson a two-year position at his institution as a dean, which allowed the founder to take care of himself and the Journal.

Moving forward, Woodson stayed the path of independence and black self-determination. To be sure, he would and did take money from foundations, usually liberal ones, but eventually that came to an end. Shortly thereafter he would wage battles with W. E. B. Du Bois and others whom he felt took the easy road by relying on funds from white sources that were trying to control black people. In the decade of the 1920s, Woodson succeeded in parlaying his salary from grant money into a successful publishing house and expanding the fundraising among black people to make real his vision of a scholarly magazine published a black controlled organization not beholding to whites.

It is unlikely he would have thought highly of ASALH putting the Journal he founded under white management in 2017. There was no financial crisis–the Journal was paying itself way in the world generating a surplus for other activities? While journal revenues were declining over time, a modest increase in dues could address the problem with an organization with over 2,000 active members. A century later the Journal is not self-managed and there is no such justification except the desire for the status that comes–in the minds of some–by being affiliated with a major white institution.