History from the Community Up

Since the 1990s, I have witnessed many talented historians, including some truly gifted ones, go without any real opportunity to practice their chosen profession. I have watched a rare few claw their way into the ranks of the tenured after being adjuncts for years. Most of us become academics because we want to think, write, and teach. Because I have always guarded myself against undo influences on my thinking–always skeptical or willing to be unconvinced–I have ever believed that the profession might have little for me. Yet I have been fortunate to ply my trade, but I was always willing to be a historian outside the academy. This is why I have always believed in ASALH and came to respect Carter G. Woodson–who did precisely the thing I thought I might have to do. He only lasted a year at Howard University and was saved for two years by his friend John Davis at West Virginia Institute. Before and after these experiences, he existed as a historian trained on his own dime and surviving outside of the academy.

The historical profession’s associations cannot imagine themselves serving anything but the academy, and then only from the top down. K-12 teachers, junior college professors, and independent scholars all feel less than welcome at gatherings, and publishing in one of the leading journals is but a dream. I spent a lot of time over thirteen years intentionally trying to be more democratic and inclusive than Woodson. Yet try as some of us did, the tendency of ASALH and all organizations occupied by academics is towards professional separation, hierarchy, and perceived prestige. Every time ASALH has tilted too far towards academics, its well-being has suffered. What is true for ASALH, I fear is true now for the entire academy.

Historians need to rethink their relationship to the university, the public, and one another. Attached to the academy, with its high cost structure, historians-in-training are running up enormous debt. Everyone who thinks about it for a moment knows that graduate programs could operate on weekends only. Societies unattached to the academy are able to publish journals at a fraction of the cost because they are free from course releases, graduate student stipends, and the ever-escalating demands of university libraries who increasingly don’t subscribe to journals anyway. Associations with their own peer-review programs could put a seal of approval on scholarship that gets preserved in their databases and then published anywhere the author, the rightful copyright holder, desires. Through local branches, historians who are from the community can promote history. Not just local history, but whatever history is being produced by the historians.

Implicit in all of this is that many of the historians, if not most, will be considered amateurs. Yet many would be history professionals outside of the academy. They will be teachers, museum workers, church historians, journalists, and former community leaders. I am convinced that America has been and remains a history wasteland precisely because we leave it to professionals rather than growing history from the community up.

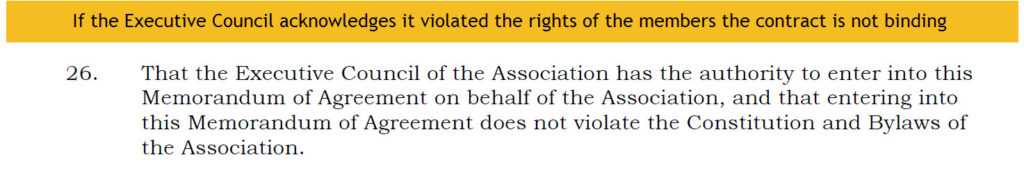

The fallout from the 101st Business Session has forced the regime to engage the membership and the Executive Council. They had been loath to do so. Yet, if members of the board had been indifferent, the people did not take kindly to being disenfranchised in the middle of our discussion of a motion to cease and desist in negotiating with any publisher. The members had doubts about the nature of the current leadership, and the leadership proved them right. The president and the vice president of membership got haughty and told us we were powerless. Turning the constitution and by-laws on their heads, they asserted us that the Executive Council, not the Business Session of the membership, was the legislative branch of our association, and that they could make decisions as they see fit. That was that, and we were, for the moment, disenfranchised!

The fallout from the 101st Business Session has forced the regime to engage the membership and the Executive Council. They had been loath to do so. Yet, if members of the board had been indifferent, the people did not take kindly to being disenfranchised in the middle of our discussion of a motion to cease and desist in negotiating with any publisher. The members had doubts about the nature of the current leadership, and the leadership proved them right. The president and the vice president of membership got haughty and told us we were powerless. Turning the constitution and by-laws on their heads, they asserted us that the Executive Council, not the Business Session of the membership, was the legislative branch of our association, and that they could make decisions as they see fit. That was that, and we were, for the moment, disenfranchised!