Reflections on the 104th Anniversary of ASALH

Yesterday, September 9th, marked the Association’s 104th anniversary. As long as Carter G. Woodson’s association lives there is hope that organization will get back right with its founder. This site exists to remind people who know ASALH that its founder’s first and foremost purpose was to create an organization for black people to publish–publish–the truth about themselves. He dedicated the remainder of his life and his resources to publishing the Journal of Negro History, now the Journal of African American History. In 2017, when ASALH’s Executive Board signed to a contract to make the University of Chicago Press its publisher, it broke faith with the past. It lost its way.

Publishing is a business, and once you leave a business, getting back into it is difficult. Most of the members on the board at the time of the sellout, did not understand what it took to publish a journal. Indeed, most some made the inane argument that we lacked a physical printing press, not know that the University of Chicago Press did not literally “press” books any more. Most of the tasks of publishing are outsourced by most publishers–even if they call themselves a “press” or a “publishing house.” Publishing is about making a publication happen financially and being legally responsible for the content. To be sure, anyone with cash and integrity can re-enter publishing, but the business of publishing also requires accomplishing all the tasks and making all the decision that make the final product viable. How this work is done and coordinated changes over time. All businesses change.

This means that as each year passes, ASALH will become more, not less, dependent on the University of Chicago or some other publisher to publish Woodson’s journal. Once fully deskilled as a publisher, ASALH will have to pay the cost of dependency. From the beginning, ASALH decided to cease self-publishing on the basis of status, not money–the new arrangements meant less, not more, net revenue. Indeed, those involved confused revenue for profit, and boasted ASALH would have the money to buy itself the things it needed. Instead, the lasting result was the loss of staffing, as predicted.

Anyone knowledgeable about academic publishing knows that a journal like Woodson’s is shrinking in university library sales, which are the source of the revenue to sustain the journal. As history shrinks as a discipline and as university libraries get their budgets cuts or frozen, they subscribe to fewer title. The carnage is real as the academy contracts, and yet ASALH, through its publishing arrangement with Chicago, is more rather than less dependent on libraries sales. The gambit by publishers with their own platforms is to make an increasing percentage of their revenue from old rather than new articles. They want to compete with JSTOR as an archive. Libraries are committed to continuing access to old journals even when they cannot afford the latest, more expense articles. The long and the sort of this that if ASALH’s publisher cannot make a living off of Woodson’s journal, it will cut it royalties to ASALH, and, if necessary, charge ASALH to publish its journal. In any event, ASALH will have to go along or find another publisher. After all, Woodson’s association is losing its publishing knowledge.

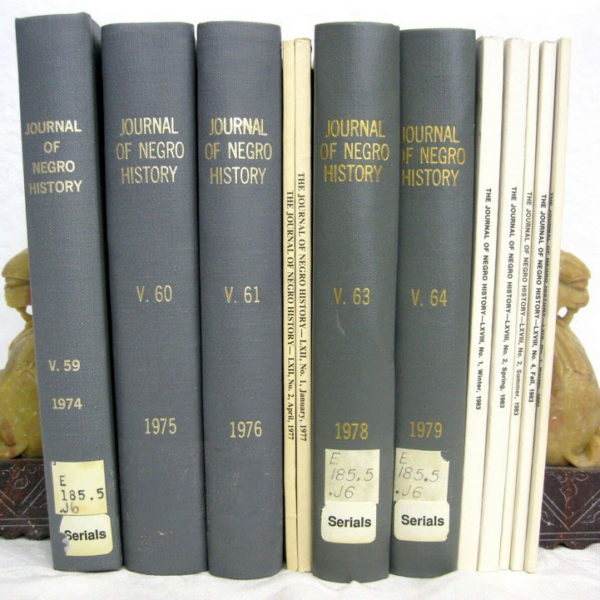

Overtime, my knowledge of academic publishing will be outdated. Frankly, I volunteered by time to ASALH for 13 years, from 2003 to 2015, because of a bookshelf I saw in Marquette’s library that looks like the one here. If you notice, there are bound and unbound issues of the journal. Moreover, there are missing numbers from the early 1980s. Those reflect neglect, not by the libraries, but by ASALH. The journal was being published irregularly, and I vowed to do what I could to change that situation if I had the chance. Everyone comes to ASALH through a door. For some it’s the journal. For others, the Black History Bulletin, the annual black history kit, or the Annual Meeting. I came for the journal and learned publishing to put the business back on its footing. This would have been impossible without V. P. Franklin, and self-publishing would have ended without me. He was the poorly paid editor, and I was the unpaid business manager. Well, ASALH is paying for the expertise of the University of Chicago because it, not ASALH, is the shot caller and gets 50% of all revenue from the labors of new editors–and the old ones too. Yes, Chicago gets a cut of all sales from 1916 to present.

What’s left of ASALH’s in-house publishing program is the Black History Bulletin. A publication for teachers by teachers, it is now one of the oldest self-published journals having been around since 1937. Those on ASALH’s board who care about the tradition of self-publishing should become involved in that publication. It is right with Woodson, and it is the hope for the future.

Now, I note that something else is different with the newer, JAAH articles on JSTOR’s platform. It appears that you can no longer see the full text on JSTOR for articles published after 2009. You can only download the pdf. Why that is unknown to me. Was this done by Chicago as the new publisher of old things? I’m clueless, and I imagine so are the powers that be at ASALH. Publishers are shot callers, not the folks who are content providers.

Now, I note that something else is different with the newer, JAAH articles on JSTOR’s platform. It appears that you can no longer see the full text on JSTOR for articles published after 2009. You can only download the pdf. Why that is unknown to me. Was this done by Chicago as the new publisher of old things? I’m clueless, and I imagine so are the powers that be at ASALH. Publishers are shot callers, not the folks who are content providers.